Bray's most famous cottage offers an ode to whimsy and nostalgia.

Chef Heston Blumenthal didn't just modernise British cooking; he reframed how we think about taste, memory and the theatricality of a meal. In the 1990s, while many chefs were leaning into continental polish, Heston was poring over historic British recipes and scientific papers, asking why things taste the way they do. The canon that followed—triple-cooked chips, liquid nitrogen at the table, and clever nods to centuries-old dishes such as "Mea Fruit" made him a household name. The Fat Duck in Bray remains the mother ship and the place where these ideas matured, having held three MICHELIN Stars for 21 consecutive years; it is still a pilgrimage for curious gourmands.

This year, The Fat Duck is celebrating its 30th anniversary—and we were eager to see if it is still ahead of the culinary curve. Set within a 16th-century cottage, The Fat Duck's dining room appears modest at first thanks to its canvas-like white walls and exposed beams, yet it's the small details that reveal the intent. Door handles are shaped like webbed duck feet, and a large pocket watch engulfs the upstairs landing. Royal-blue carpets and a procession of glass-fronted wine cabinets bloom from frosted to clear as you pass. The windows are blacked out, so the table becomes a stage. Overhead, spotlights shift in hue and intensity with each course, creating a subtle effect that is dreamlike while entirely in service of the story.

Service is superb. There is alchemy and theatre, delivered with generosity rather than stiffness. The team choreograph the pace of the meal, narrating the story of each dish like a storyteller, while leaving space for conversation.

The Fat Duck's Journey menu celebrates the restaurant’s thirtieth anniversary and is charted as an “itinerary” rather than a list. It begins with an amuse-bouche of nitro-poached vodka-lime “apéritif." Egg-white mousse is piped into liquid nitrogen, transforming into a crisp meringue that shatters, perfumes and vanishes in a heartbeat. It's a playful nod to the restaurant's early experiments with nitrogen and a reminder that cocktails need not arrive in a glass. A second nibble, aerated beetroot with horseradish cream, is a study in texture as much as flavour.

Blumenthal's fascination with historic British tastes punctuates the early chapters. Red Cabbage Gazpacho arrives with mustard ice cream and compressed cucumber, the brassica tang threading through creamy sweetness with surprising poise. Then comes the most mischievous plate of the day: Breakfast in a Bowl. Cereal that tastes like a full English. You lift the cardboard variety pack to find scrambled-egg custard and a jellied tomato consommé, while the "cereals" crunch with the flavours of sausage, bacon, fried bread and tomato. It's witty with a carefully judged balance of salt, umami and warmth, and a delightful tug at childhood nostalgia.

The next course turns to the coast. "The Sound of the Sea" invites you to slip on headphones and listen to the waves and gulls while a beachscape tableau unfolds: halibut, razor clams, and hamachi are laid over an edible shoreline of seaweed, foam, and "sand" made from miso-tinted breadcrumbs. The sashimi-like clarity of the fish, the iodine lift of sea vegetables and the crunch of the sandbar create a complete mouthful. A whimsical "Crab & Passionfruit 99" ice cream cone follows, in which delicate crustacean and tropicality offer a sweet‑salty interplay against a veil of crisp chocolate.

Back inland, "A Walk in the Woods" layers textures of mushrooms with bark, portobello mushroom "soil" and roasted mealworms for crunch. It sounds outré, but it tastes like autumn in its earthy, savoury, and gently smoky complexities.

The meat course is a measured nod to the Sunday table, showcasing lamb with cucumber two ways (fresh and smoked) with a clean line of mint jelly. Here, the trickery recedes. The lamb is tender and confident, the smoke is delicate rather than dominant, and the cucumber's coolness reins in the richness.

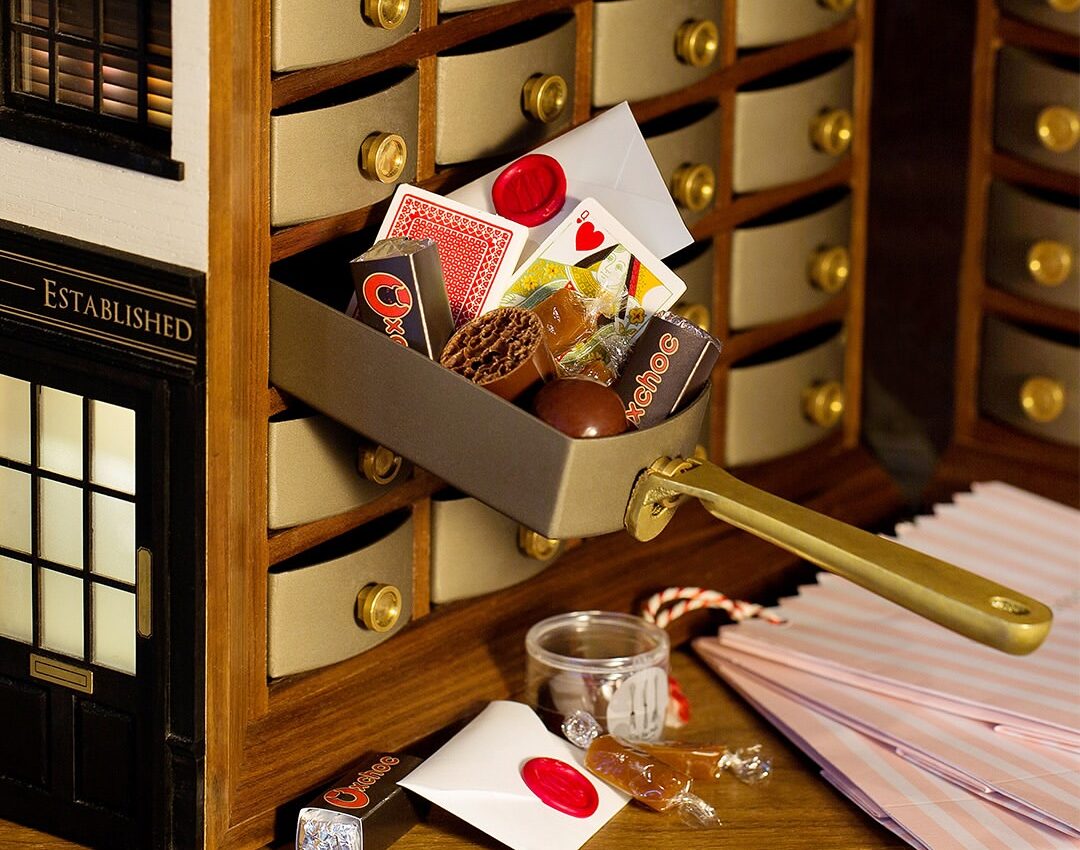

Desserts restore the sense of wonder. "Off to the Land of Nod" is an affectionate ode to bedtime with a Horlicks-scented preparation made with coconut blossom milk, an eye mask to heighten anticipation, and edible "pillows" that levitate above the table by magnetism. It's warm and soothing rather than showy. Then comes the finale: the Sweet Shop. A diorama-like cabinet appears, and when a coin is fed into the slot, drawers spring open to reveal confections, from a pecan-pie toffee wrapped in edible cellophane, to a dainty tea cake, and a playing card cast in white chocolate and filled with raspberry. It's a child's treasure box rebuilt for adults; part Willy Wonka, part Victorian fairground, and a final salute to childhood wonder that will send you out of the restaurant smiling.

Across the meal, what impresses most is how Blumenthal's ideas are anchored in flavour. The headphones, magnets and colour-changing lights create mood, but the plates succeed because the cooking is exact: consommés are limpid, gels clean, and temperatures precise. The kitchen aims for accumulation, letting quiet technical mastery build course by course until the narrative lands.

The Fat Duck is whimsical and nostalgic, but never frivolous. It remains a uniquely British dining experience that still surprises long after its headline-grabbing innovations became part of the culinary mainstream. If you're looking for a meal that balances memory with method, Bray's most famous cottage maintains a reputation for excellence decades after its debut.

GO: Visit https://thefatduck.co.uk for more information.